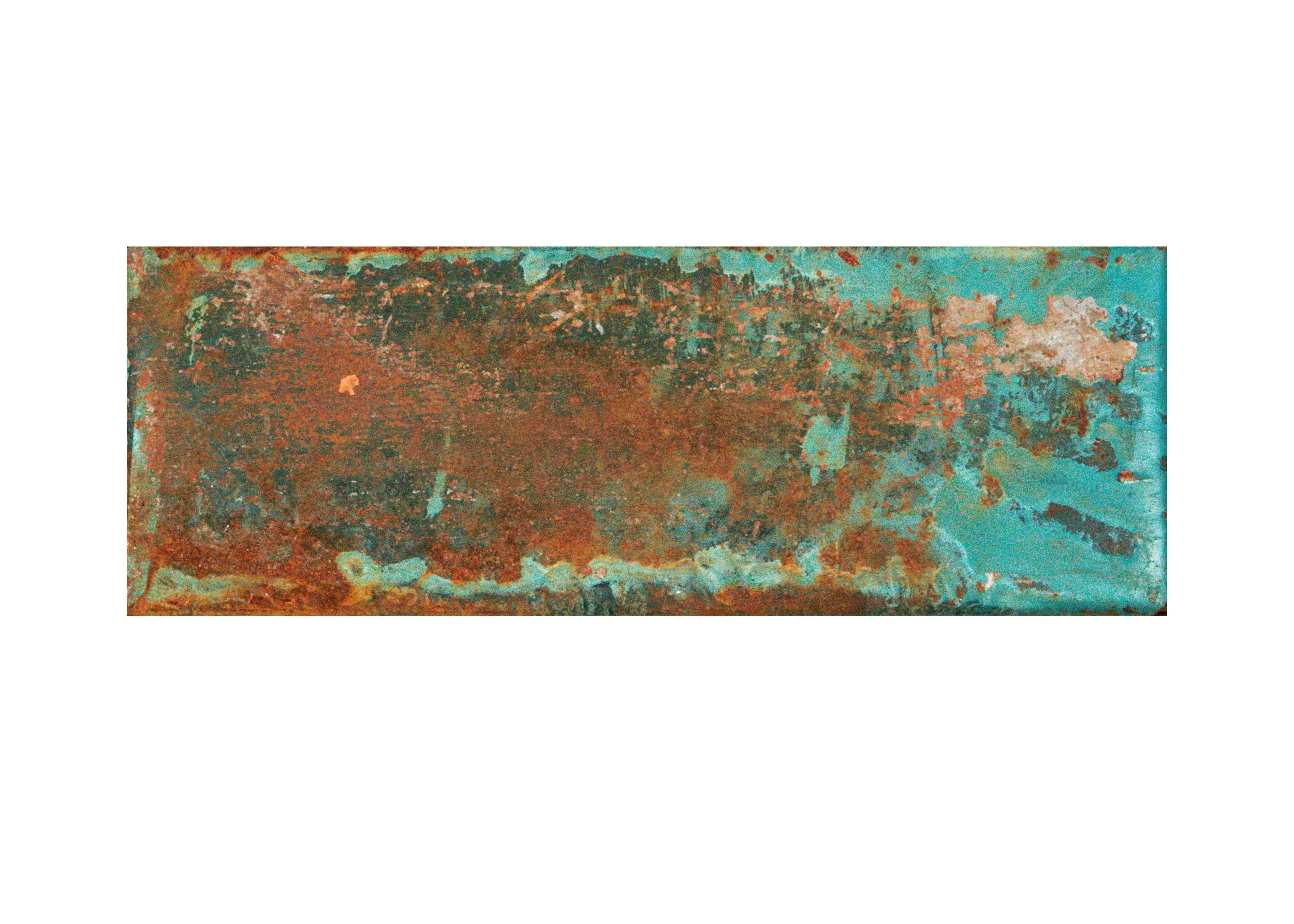

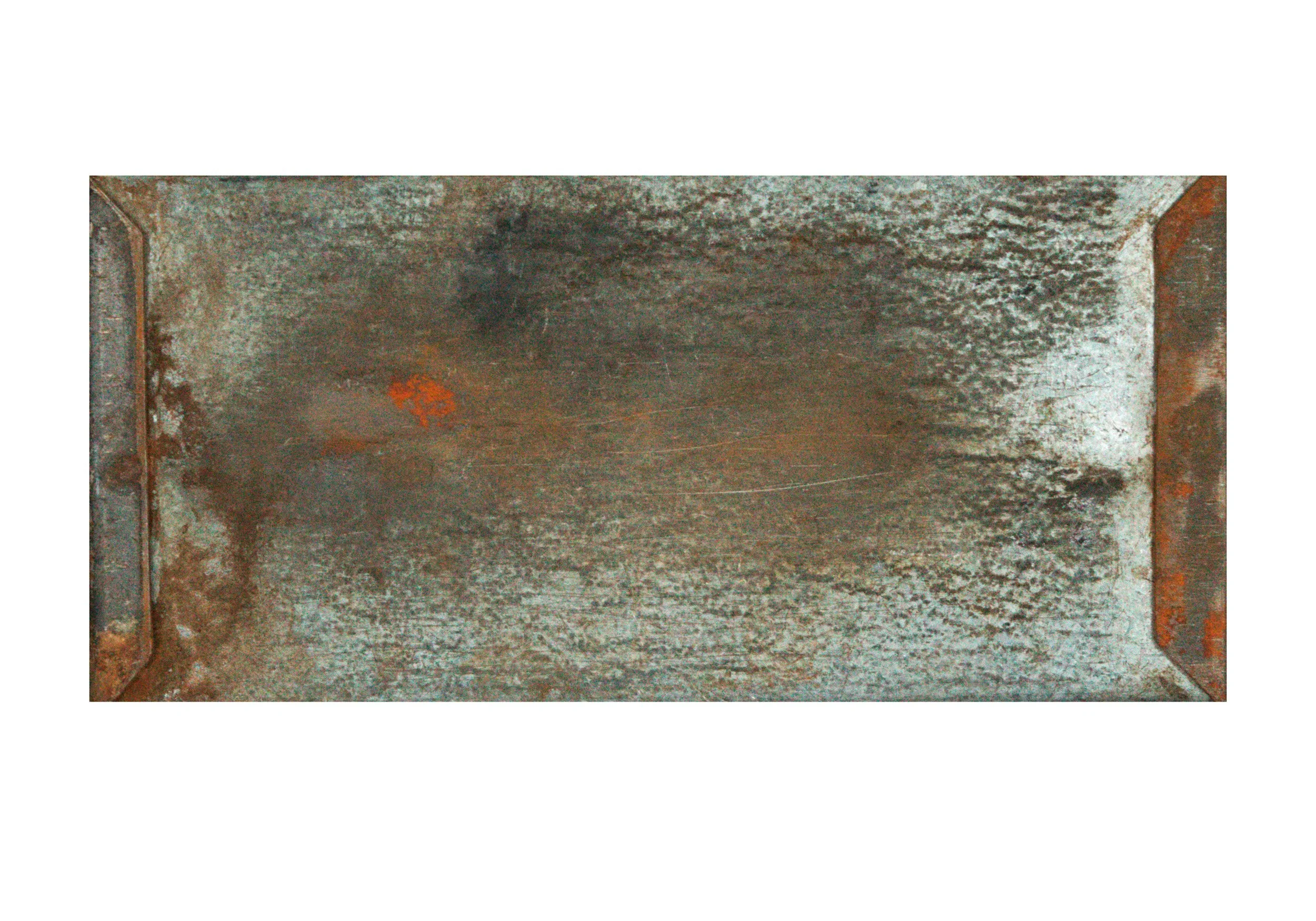

Forgotten Treasures incorporates decades long forgotten, and seemingly untouched, contents from found metal cabinets with the traces and stories these items left behind: documenting the passing of time, a reminder of the fragility of temporal existence.

Essay by Dr Andrew Dearman

An outline around a seemingly empty space

How do we think things that have come adrift from their origin—from places where they once sat accumulating dust for decades—leaving a trace of their presence? What happens to those traces and the places of origin themselves when they become emptied out of the things that they once contained? These are some of the questions that come to mind with Anne Stevens’ work.

Our response here, is informed by what Stevens refers to as an ‘intrigue in the affective qualities present in the process of transformation’ and by a fascination with an objects/thing’s consequential memory, fragile beauty and documentation of time.[1]

Our response is also informed by our own experience of things in the world. John Berger observes in The Shape of a Pocket, that ‘[w]e live our daily lives in a constant exchange with the set of daily appearances surrounding us – often they are very familiar, sometimes they are unexpected and new, but always they confirm us in our lives. ... What we habitually see confirms us.’[2]

Berger refers to the appearances of everyday things that we become blind to, due to their familiarity—describing the space between us and the things that envelop us as dynamic and lively—a liveliness that we are similarly blind to, because of our familiarity with things. However, things that we habitually touch also confirm us in our lives—the things that we put in a drawer and forget, absent-mindedly put somewhere, lose, go searching for, find again, put back in a drawer and forget again—a repetition of forgetting and remembering.

Art of the last century has turned away from seeing in favour of other senses like touch, which of itself, according to some theorists who draw on physics, is an impossibility. In On Touching—the Inhuman That Therefore I Am Karen Barad equates doing theory within the physics of touch—to theorise is to touch, to make contact, while at the same time actual contact is an impossibility.

You may think you are touching a coffee mug when you are about to raise it to your mouth, but your hand is not actually touching the mug. … [W]hat you are actually sensing, […] is the electromagnetic repulsion between the electrons of the atoms that make up your fingers and those that make up the mug. … Try as you might, you cannot bring two electrons into direct contact with each other.[3]

The affective qualities that Stevens directs us toward reside within this dynamic liminal space that Berger and Barad infer—a space of and in between forgetting and remembering. Once in a hand—once in a drawer. Only here, the person remembering isn’t the person who forgot. A second-hand vicarious form of memory work is at play, through our experience of picking something up, turning it over in our hand, experiencing its weight, texture, temperature. A consequential memory, fragile beauty and documentation of time presented here as a memory trace.[4]

Written by Dr Andrew Dearman

[1] Stevens, A. Forgotten Treasures, Sauerbier House 2025 Exhibitions Schedule,

City of Onkaparinga, 2025, p.16

[2] Berger, J. ‘Opening a Gate’, in The Shape of a Pocket, Bloomsbury, London, 2001, p.5

[3] Barad, K, On Touching—the Inhuman That Therefore I Am (v1.1) 2012,

https://planetarities.sites.ucsc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/400/2015/01/barad-on-touching.pdf

[4] Stevens, A. Forgotten Treasures, 2025, p.16